By Catia Malaquias

Disability, unlike many other human variables (e.g. wealth, skin colour, culture, religion, language etc) is not usually passed from generation to generation. Most parents do not have direct experience of living with disability, yet they find themselves making life-influencing decisions for their child which are affected by the limits of their own understanding of disability.

Many people with disability say that they are restricted, not so much by their physical or mental impairment – in other words, the way their body or mind works – but by the failure of their community and environment to take into account different bodies and ways to function, and to accommodate and adjust for those differences. This idea that the way a person’s environment is built or organised can be “disabling” underlies the social model of disability, which in turn underpins the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD). It sees disability as part of human diversity. It also underlies the principles of “inclusive education” – students with disability being educated in regular classrooms alongside and together with their same-age regular peers, receiving education delivered in a way that is accessible to each of them.

Yet for much of society and its institutions, the medical model of disability remains predominant in how they respond to a person with disability – namely, as a person whose impairment is to be medicalised – diagnosed, treated and to the extent possible remediated. The goal being to “fix” the individual to attain ‘normality’ – rather than to make environmental and social adjustments to better include the individual in society.

Our modern education system only attempted to extend education to students with disability comparatively recently. It did so, and largely continues to do so, through the prism and restrictions in mindset of the medical model of disability. “Special education” began as an add-on to institutions set up early-mid last century to institutionalise and segregate children with disability from society, their communities and their families.

But the segregating trappings of “special education” have proven resistant to change. Governments, private ‘special education’ providers, school administrators, the teaching profession, medical and allied health professionals etc have maintained the logical connection between “special needs kids” and segregated “special education” settings, all in a vacuum from and against the objective research evidence. From a simple fear of systemic change (because segregation is what has been done for so long) to vested private interests seeking to maintain the businesses built around segregated service delivery – these stakeholders “market” segregated education against the corroborating background of a general education system that continues to “gatekeep” and resist educating students with disability, all the while disowning their responsibility by characterising the decision to educate a child in a segregated “special” school or class setting as one for the parents to make – “parental choice“.

When decades of evidence have shown that segregated education disadvantages students with disability by producing inferior academic and social outcomes in a “low expectations” environment, then it is fair to say that the ‘choice’ of parents to segregate their children in a very real sense can be “disabling” in itself. The failure of Governments and professionals to better guide parents in their decision-making is unconscionable – even negligent.

Assertion No. 1 – “Your child has ‘special needs’“

No, they don’t. We are all human and we all have regular human needs but the way we have those needs met is as diverse as humanity itself. We all need to be loved, nurtured, clothed and have shelter, to get around, to be educated, to have social relationships, to access the community, to belong and feel valued and so on.

A person who walks has the same need for mobility as a wheelchair user, but that same need is met in a different way for both of them. A child with an intellectual disability has the same fundamental need to be educated as a child with typical intellectual function, but they may need to have curriculum content delivered in a different way, so their common need to learn may be met in different ways. An autistic young adult has the same need to have social relationships as a neurotypical young adult, but how they each satisfy that need can look very different depending on a range of factors, including disability. A person with a disability may require some accommodations or more assistance – maybe significant assistance – in meeting a particular need, especially when their environment has been predetermined without regard for their disability, but ultimately they are still seeking to meet basic human needs.

But surely “special needs” is innocuous, right? I mean, “special” is a positive adjective, it’s nice. Again, no. The phrase “special needs” is commonly used as a euphemism to refer to a person with a disability (particularly intellectual or cognitive disability and, more often than not, a child) and there is nothing innocuous about the mentality that goes that phrase. Most adults with disability do not self-identify as having “special needs” and find this euphemism generally offensive or condescending. A study recently published in Cognitive Research: Principles and Implications empirically tested general public attitudes toward the term “special needs” and the term “disability”. The study found that “persons of all ages are viewed more negatively when they are described as having ‘special needs’ than when they are described as having a disability or having a certain disability”. You can link to the study here and a blog article from the study’s author here.

If you think about the use of the adjective “special”, it has become shorthand for describing places set aside for people with disability, e.g. “special schools”, “special education units”, “special workshops”, “special homes”, etc. There are hundreds, if not thousands, of websites and Facebook pages dedicated to people with “special needs” and to the parents of children with “special needs”. The phrase “special needs” is regularly used by the media – it is common language. It is an industry in itself.

Although human diversity, the social model of disability and inclusion as human rights framework concepts are developing traction, for much of society the “special story” still goes like this:

A child with “special needs” catches the “special bus” to receive “special assistance” in a “special school” from “special education teachers” to prepare them for a “special” future living in a “special home” and working in a “special workshop”.

Does that sound “special” to you?

In the minds of many in our society a “special needs” label is effectively a one-way ticket to a separate, segregated, low-trajectory pathway through life.

The word “special” is used to sugar-coat segregation and societal exclusion – and its continued use in our language, education systems, media etc. serves to maintain those increasingly antiquated “special” concepts that line the slippery path to a life of exclusion and low expectations.

The logic of the connection between “special needs” and “special [segregated] places” is very strong – it doesn’t need reinforcement – it needs to be questioned and broken.

Further, the “special needs” label sets up the medical “care” model to disability, rather than the social inclusion model of disability. It narrows and “medicalises” society’s response to the person by suggesting that the focus should be on “treating” their “special needs”, rather than on the person’s environment responding to and accommodating the person – including them for the individual that they are.

There is another insidious but serious consequence of being labelled (as having or being) “special needs”. The label carries with it the implication that a person with “special needs” can only have their needs met by “special” help or “specially-trained” people – by “specialists”. That implication is particularly powerful and damaging in our regular schooling systems – it is a barrier to regular schools, administrators and teachers feeling responsible, empowered or skilled to embrace and practice inclusive education – the education of students with disability alongside their same age peers in regular classrooms. Accordingly, the phrase perpetuates attitudinal resistance – a “can’t do” attitude – to inclusive education, so critical to maximising social and economic outcomes for people with disability.

The label of “special needs”, serving by definition to segregate or exceptionalise people with disability, is inconsistent with recognition of disability as part of human diversity. In that social framework, none of us are “special” as we are all equal siblings in our diverse family of humanity.

It is time to stop calling disabled people “special” so that many can justify (without more than that exceptionalising and stigmatising label) sending them somewhere else – to “special” places.

Assertion No. 2 – “Children with disability do better in ‘specialist’ settings”

For over 40 years, the body of relevant research into education of students with disability has overwhelmingly established inclusive education as producing superior social and academic outcomes for all students. Further, the research has consistently found that academic and social outcomes for children in fully inclusive settings are without exception better than in segregated or partially segregated environments (e.g. “education support units” or “resource classrooms”). Unfortunately segregated education remains a practice which continues to be suggested to families and educators as an appropriate option, despite having virtually no evidence basis.

The most recent comprehensive review of the research was undertaken by the Alana Institute and presented in an international report entitled “A Summary of the Evidence on Inclusive Education“ released in 2017. The Report was prepared by Dr Thomas Hehir, Professor of Practice in Learning Differences at the Harvard Graduate School of Education in partnership with global firm Abt Associates.

The Report is essential reading for education administrators, teachers and parents in documenting the results of a systematic review of 280 studies from 25 countries.

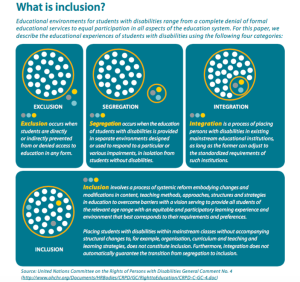

The Report defines inclusive educational settings in accordance with General Comment No. 4 (The Right to Inclusive Education), recently released by the United Nations Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. In particular, the General Comment defines non-inclusion or “segregation” as the education of students with disabilities in separate environments in isolation from students with disabilities (i.e. in separate special schools or in special education units co-located with regular schools). [p3]

The Report recognises that the growth in inclusive educational practices stems from increased recognition that students with disabilities thrive when they are, to the greatest extent possible, provided with the same educational and social opportunities as non-disabled students [p4]

The Report also acknowledges the significant barriers of negative cultural attitudes and misconceptions amongst school administrators, teachers, parents (including some parents of children with disabilities) and communities to the implementation of effective inclusive education and notes the need for general societal education as to the benefits of inclusive education.

Key findings of the Report include that there is “clear and consistent evidence that inclusive educational settings can confer substantial short and long-term benefits for students with and without disabilities”. [p1]

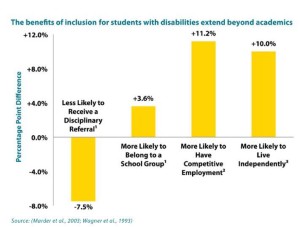

- “A large body of research indicates that included students with disabilities develop stronger skills in reading and mathematics, have higher rates of attendance, are less likely to have behavioural problems, and are more likely to complete secondary school than students who have not been included. As adults, students with disabilities who have been included are more likely to be enrolled in post-secondary education, and to be employed or living independently.” [p1]

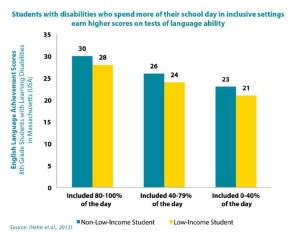

- Multiple reviews indicate that students with disabilities educated in general education classrooms outperform their peers who have been educated in segregated settings. A 2012 study by Dr Hehir examined the performance of 68,000 students with disabilities in Massachusetts and found that on average the greater the proportion of the school day spent with non-disabled students, the higher the mathematic and language outcomes for students with disabilities. [p13]

- The benefits of inclusion for students with disabilities extend beyond academic results to social connection benefits, increased post-secondary education placement and improved employment and independence outcomes. [p15] There is also evidence that participating in inclusive settings can yield social and emotional benefits for students with disabilities including forming and maintaining positive peer relationships, which have important implications for a child’s learning and psychological development. [p18] Again, there is a positive correlation between social and emotional benefits and proportion of the school day spent in general education classrooms. [p19]

- The Report states that “…research has demonstrated that, for the most part, including students with disabilities in regular education classes does not harm non-disabled students and may even confer some academic and social benefits. … Several recent reviews have found that, in most cases, the impacts on non-disabled students of being educated in an inclusive classroom are either neutral or positive.” [p7] Small negative effects on outcomes for non-disabled students may arise where a school ‘concentrates’ students with severe emotional and behavioural disabilities in the one class (itself a form of segregation) rather than distributing those students across classrooms in their natural proportions. [p9]

- “A literature review describes five benefits of inclusion for non-disabled students: reduced fear of human difference, accompanied by increased comfort and awareness (less fear of people who look or behave differently); growth in social cognition (increased tolerance of others, more effective communication with all peers); improvements in self-concept (increased self-esteem, perceived status, and sense of belonging); development of personal moral and ethical principles (less prejudice, higher responsiveness to the needs of others); and warm and caring friendships.” [p12]

- An extensive recent meta-analysis covering a total sample of almost 4,800,000 students has also confirmed the finding that inclusive learning environments have also been shown to to have no detrimental impact, and some positive impact, on the academic performance of non-disabled students.

You can read the full Report here.

Assertion No. 3 – “Special schools are needed – and parents need to be able to choose them – because ‘one size does not fit all‘”

It is true that ‘one size does not fit all‘ and that is exactly why we need to ensure that we have an education system that is universally accessible and inclusive of every student regardless of ability or function. The United Nations Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities in its recent General Comment No. 4 to Article 24 (The Right to Inclusive Education) outlined the core features of an inclusive education system, including a “whole person” approach [paragraph 12(c)]:

“Whole person approach: offers flexible curricula, teaching and learning methods adapted to different strengths, requirements and learning styles. This approach implies the provision of support and reasonable accommodation and early intervention so that they are able to fulfil their potential. The focus is on learners’ capacities and aspirations rather than content when planning teaching activities. It commits to ending segregation within educational settings by ensuring inclusive classroom teaching in accessible learning environments with appropriate supports. The education system must provide a personalized educational response, rather than expecting the student to fit the system.”

General Comment No. 4 also defined the practice of “integration” as distinct from “inclusion”. Integration refers to “placing persons with disabilities in existing mainstream educational institutions, as long as the former can adjust to the standardized requirements of such institutions.” In other words, if a general education system provides a “one size fits all” model then it is not an inclusive system. Those students that do not “fit the system” are then pushed out into the alternate”special” segregated system. A genuinely inclusive education system which is academically and socially accessible to all students – which caters for all – does not need an alternate parallel system, especially one that has been found for decades to produce inferior outcomes for those students.

While the notion of “separate but equal” was deemed discriminatory in the context of racial segregation in the US education system, as long ago as the 1954 US case of Brown v Board of Education, the topic of “parental choice” in segregating students with disability is one that often polarises the community of parents of children with disability, and indeed, the wider community. Rarely however does it polarise the disabled community, who continue to fight for inclusion in every area of life and whose fundamental human right it is to access an inclusive education.

But in the same way that racial segregation in education, and indeed the denial of education to girls, have been clouded by cultural beliefs, education of students with disability equally occurs within the context of pre-conceived stereotypes and subconscious bias in the decision-makers themselves, the absence of quality information and advice, and where self-justification can sometimes compromise the capacity to reflect and re-evaluate.

Should parents have the right to choose educational segregation of their child on the basis of their disability?

That is, whether their child attends a special school, a special unit co-located with a mainstream school rather than a regular school.

In our society, we recognise that it is parents who should determine, in the first instance, what is in their child’s best interests. When it comes to educational decisions about their child, most parents recognise these types of decisions as critical to their child’s best interests; and want to exercise choice to give their child the best chance of success in life.

When a child has a disability, the decisions that parents make are in some ways even more significant for the long-term outcomes of the child.

Governments, many disability associations, national parenting websites and “special needs” magazines present the decision of the learning environment for a child with disability as one of “parental choice” – a choice between “equally good” options for the parents to make in light of the circumstances of their child. By providing a range of educational environment options, they say that parents can make the choice that is best for their child. Like shoes, “one size doesn’t fit all” – the mantra of the “parental choice” view.

The choice is presented as a natural compromise or trade-off between a sliding-scale of “specialist support” for the child – the more segregated the environment, the more specialist supports available (i.e. smaller classes with higher specialist staff-student ratios) – but with a corresponding reduction in social and academic contact with same-age non-disabled student peers. The message, consistent with societal expectations founded in a long-history of excluding, institutionalising and segregating people with disability, is that children who require more significant supports need more “specialist” attention in more “specialised” environments and that is more important – and more beneficial – than social and academic learning with same-age regular peers in a regular school environment. The thing is, the empirical evidence doesn’t support this view.

An article I recently read sought to justify “parental choice” as to educational segregation as being akin to the natural variety in working environments – big corporate office in a CBD building, a warehouse in a suburb or a home-office – they were all places from which people do good work and the colour of the money earned is the same. By analogy, students in segregated learning environments still do “good learning” like everyone else and get something out of it.

But the education of students with disability is not some life-style decision to be made by parents on poor information and subject to their own limiting pre-conceived expectations, guided by medical professionals conditioned to see disability as deficits to be “treated” and “advised” by school administrators operating in an education system designed to preserve the status quo.

Choosing a segregated specialist classroom is not like choosing a private school over a public school, or a Catholic school over a non-denominational school. With over 40 years of research evidence overwhelmingly in favour of educating disabled students in the same classrooms as their non-disabled peers and demonstrating unequivocally superior long-term academic, social and economic outcomes, we know that the decision to segregate is a decision that goes to the quality of the education – and therefore it goes to equality of educational opportunity and provision – and therefore to discrimination against segregated children with disability as a group.

They are not things that are sacrificed in choosing between the usual “philosophies” and preferences in education options (public v private, denominational etc) – they are things sacrificed in choosing segregation, a mode of delivering education to students with disability, against the objective research evidence.

Inclusive education is the optimal and most direct pathway to living, working and fully participating in the community, whilst expanding diversity and reciprocal acceptance of diversity at each stage – in classrooms, workplaces and society itself.

The “special” path, lined by a well-meaning culture of low expectations and outcomes, is too often a sugar-coated path to social and economic marginalisation and exclusion – and serves to further entrench outdated societal attitudes to disability.

Inclusive education – a human right of people with disability, not parents

As a matter of international human rights, the rights of parents to choose is subject to the right of their child to an inclusive education – to an education alongside their same-age typical peers in a regular classroom with appropriate supports and curricula adjustments – in accordance with Article 24 of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities – to which over 170 countries are parties. In fact, the UN recently affirmed this position in defining and explaining the right to inclusive education in General Comment No. 4 , stating that inclusion education is:

“A fundamental human right of all learners. Notably, education is the right of the individual learner, and not, in the case of children, the right of a parent or caregiver. Parental responsibilities in this regard are subordinate to the rights of the child.”

The idea that parental rights to choose have some limitations is not radical. Government law and policy both enable and restrict educational options in a range of ways. For example, parents don’t get to choose not to educate girls or to choose that girls shouldn’t be taught academic subjects, even though these beliefs were not uncommon that long ago and parents did exercise educational choices between girls and boys in that way. Nowadays, we see it for what it is – educational discrimination. Similarly, children with some disabilities used to be denied access to any education. As a society we no longer believe that is acceptable.

“Parental choice” in the context of considering segregated schooling options should be seen for what it is – a decision to concede, to segregation, the right of the child to an inclusive education.

There are many reasons for this and in many cases parents are in fact responding to pragmatic limitations and deficiencies of the regular education system. The fact is, many children with disability and their families have very poor experiences in regular settings for a range of reasons – from “gatekeeping” by schools that don’t welcome and support their child, to poor practices, safety concerns, inadequate responses to bullying and social vulnerabilities, to school cultures that are not inclusive of students with disability and their families. Ironically, these failures are sometimes attributed to “inclusive education” itself – in reality they are due to a lack of inclusiveness, not because if it.

While every parent would like to make choices in their child’s best interest, when it comes to education of children with disability, the range of options that some families are provided with are so poor that parents are effectively forced to make a “least worst” choice – between a low outcomes segregated setting (i.e. a special school or education support unit) that welcomes them and their child or a regular setting that fails to welcome and accommodate their child.

In most cases, parents accept segregation of their child because the regular education system did not, would not or was not expected to provide the appropriate supports and adjustments – which under Article 24 it is obliged to do.

I don’t see “parental choice” in this context as a free choice between “equal options” made on a fully-informed basis – I don’t see “one size doesn’t fit all” as a legitimate analogy.

I see “parental choice” as Hobson’s choice for many parents – it is an exercise in “parental concession” – parents conceding the rights of their child to an inclusive education to an education system unwilling or unable to transform itself into a system that is accessible to all children and which accommodates their diverse functional needs – indeed a system that should assume and accommodate the diverse needs of ALL children, whether or not they have a disability.

Segregation is the price many parents are transacting, and that their children with disability are paying, for an education system that excluded children with disability since its very beginnings and that continues to resist their inclusion today.

This systemic leakage of students to segregated settings as a result of these factors – politically dressed as driven by “parental choice” – serves to preserve the status quo, namely the parallel segregated “special” system alongside a general education system that provides only limited and conditional access to students with disability.

The flow of students to segregated settings is not evidence of parental support for segregation of their children. It is not. It is the symptom of how far the regular education system has to go in order for it to be a genuinely inclusive system.

Governments, many disability associations, national parenting websites and “special needs” magazines cannot take a superficial approach to the issue of segregating students with disability. It is irresponsible to merely leave such a critical life-influencing decision to “parental choice”. Any discussion of the issue must recognise the relevant human rights framework, the right of each child to an inclusive education and must reference now long-standing evidence-based research and information.

*This article is based on three earlier articles published by Starting with Julius. It draws together commentary on three key assertions that should be examined by anyone concerned in the education of students with disability, particularly parents.

[Cover photo © Cel Lisboa]

Thank you for visiting our website. You can also keep up with our mission for #adinclusion by liking our Facebook page or following us on Twitter @StartingWJulius