By Catia Malaquias

What does Julius have in common with the Mona Lisa, Paul Keating and Marilyn Monroe?

Not that much – but this week a painting titled “Starting With Julius” was submitted to the West Australian Black Swan Prize for portraiture by the artist Federico Medina. It was a portrait of my son Julius, the first SWJ Ambassador. In Mr Medina’s words he wanted to capture “Julius’ enthusiasm for full participation in life, whilst recognising that social, educational and economic inclusion remains an unrealised human right for many people with disability.”

The portrait was Mr Medina’s personal expression of support for the work of Starting With Julius.

I was first approached by Mr Medina, a very talented Mexican-Australian artist, after he read an article in the media about Julius’ modelling for mainstream brands and the work of Starting With Julius in promoting inclusion of people with disability. He later disclosed to me that he has a beloved nephew back in Mexico who also has Down syndrome and that he found capturing Julius authentically both technically challenging and emotional.

I was thrilled that someone wanted to paint Julius’ portrait. But what really engaged me was the opportunity to memorialize a child with Down syndrome in a portrait painting, given cultural attitudes to disability and the fact that portraiture has historically been about celebrating those our society values most – people of wealth, power or social influence and people who embody accepted ideas of beauty.

Like inclusive advertising, this represented an opportunity to disrupt cultural ideas around disability and as to who gets to be valued and celebrated. And when it comes to devaluation, people with Down syndrome are right up there.

For example, rates of termination of pregnancies following identification of Down syndrome are estimated to be around 90% in Australia and many other countries – Iceland reputedly nears 100%. In some countries governments and medical practitioners celebrate the fact that no babies with Down syndrome are being born. France is currently the subject of a complaint to the European Court of Justice about its decision to ban from television a video about the life potential of people with Down syndrome because it could cause discomfort to mothers that have chosen to terminate their pregnancies.

Many children with Down syndrome born today continue to face significant barriers in accessing education in regular schools in Australia – just ask Pauline Hanson. In some countries, children with Down syndrome are only allowed to attend segregated schools and in others, they are denied access to any form of education at all. Rates for employment of people with Down syndrome in Australia remain shockingly low and in many cases the only “opportunities” are for employment in segregated workshops for as little as $1 per hour – despite the Australian minimum hourly wage of $17.

As the parent of a child with Down syndrome, these statistics primarily speak to me of how our society continues to perceive people like my son and its lingering “low expectations”,  together with associated prejudice and outdated stereotypes, that continue to undermine, compromise and delay inclusion and participation for people with Down syndrome and other disability.

together with associated prejudice and outdated stereotypes, that continue to undermine, compromise and delay inclusion and participation for people with Down syndrome and other disability.

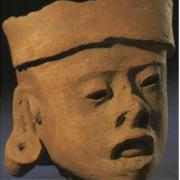

What is also interesting however, is the evidence of Down syndrome in human history as reflected in art. For example, some experts believe that there is material evidence from prehistory that depicts people with Down syndrome.

In painting, examples considered to depict subjects with Down syndrome date back to the 16th Century but perhaps most intriguing to me are a series of religious paintings attributed to Italian artist Andrea Mantegna (1431-1506) that in some cases depict the infant Jesus as a baby with physical characteristics resembling Down syndrome. It is believed that Mantegna had a child with Down syndrome, as did one of his patrons, the Gonzanga family. Another famous example is the Flemish painting “The Adoration of the Christ Child”, by a follower of Jan Joest of Kalkar, which depicts an angel and a shepherd child with facial features suggestive of Down syndrome.

It is a privilege to see Federico Medina’s portrait of Julius come to life and add to a very small but important body of art that evidences, throughout the ages, an artistic challenge to society’s perspective of people with Down syndrome and disability – as a proud celebration of their value, beauty and diversity.

It is a privilege to see Federico Medina’s portrait of Julius come to life and add to a very small but important body of art that evidences, throughout the ages, an artistic challenge to society’s perspective of people with Down syndrome and disability – as a proud celebration of their value, beauty and diversity.

I should also add that the subject-in-residence, Julius – who struggles to stand still, let alone sit still – thinks Mr Federico did a pretty good job … “Look! It’s Julius!”

[Cover photo © Starting With Julius]

Thank you for visiting our website. You can also keep up with our mission by liking our Facebook page or following us on Twitter @StartingWJulius