By Catia Malaquias

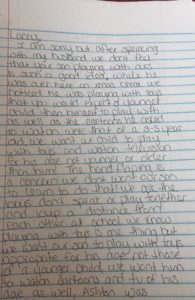

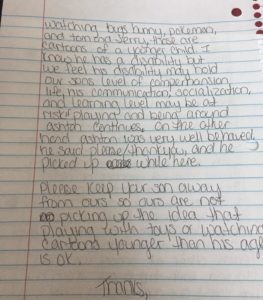

A Facebook post yesterday by Lacey Brandenburg has well and truly gone viral. She posted a copy of a two-page letter her son with intellectual disability was given by his “only” friend at school – a letter penned by the mother of his school friend to Lacey concluding with the following paragraph:

“Please keep your son away from ours so ours are not picking up the idea that playing with toys or watching cartoons younger than his age is OK.”

While some have speculated as to the authenticity of the letter – its authenticity is largely irrelevant – the fact is that the letter and the surrounding story is believable, particularly to parents of a child with disability, because to varying degrees and in a range of contexts, they encounter these sorts of attitudes.

As Lacey says in her post:

“ … this is being posted to teach people what parents with … children [with disability] face and what they deal with!”

As a parent of a child with a disability, I know what it is to feel hyper vigilant about the nature, quality and reciprocity of my son’s friendships – about his social inclusion and the added risks that he faces of experiencing bullying and exclusion. The clichéd monitoring of birthday invitations (and exclusions) and numbers of playdates. Receiving less invitations than the average is typical. Receiving invitations with an expectation of supervising your child is also typical – the expectation often borne out of fear more than necessity. Receiving broader invitations restricted to your child’s non-disabled siblings is also typical.

The reality is that many parents of non-disabled children feel uncomfortable or “unskilled” to accommodate a child with a disability.

It is a reaction that is unfortunately also in common with many teaching professionals.

The difference in degree in Lacey’s story is that the parents who authored the letter lacked so much sensitivity, insight and tolerance that they took the step of documenting their misguided fears and their prejudice in writing and as a communication – not to the school or teacher – but to the parents of the child with a disability – with the added callousness of using the children involved as the messengers.

The message is no less than a confronting, direct request from another parent that speaks from a position of ableist entitlement – and by definition that places no value or consequence on the rejection and exclusion of the other child.

Creating school environments in which all students, including students with disability, belong and are valued – environments in which they are academically and just as importantly socially included depends on the examples set for students by their teachers and, perhaps more importantly, by their parents. The implicit ableist bias against people with disability that most people in society carry is largely attributable to the attitudes of their parents towards people with disability.

There is a huge need for Governments to educate the community and foster understanding about the importance of social inclusion – particularly for people with disability.

The attitudes of parents of non-disabled students has a direct bearing on the enrolment and retention of students with disability in mainstream schools. When parents of students with disability do not feel that their child is welcome in the school community – when they themselves do not feel welcome – that goes a long way to justifying in their mind the merits of moving their child to a segregated “special” learning setting. A setting where they will find other parents with similar exclusionary experiences – which will alleviate their own sense of social discomfort.

Unfortunately, the research evidence demonstrates that the cost of giving up on schooling in a regular mainstream classroom is inferior long-term academic, social, economic and independence outcomes for segregated students with disability.

Parental attitudes – including attitudes of parents of non-disabled students within the school community – are a key factor operating (indirectly) in denying students with disability their right to receive an inclusive education along-side and together with their same-age peers.

As parents, each of us gets to decide – we can either be barriers, or facilitators of a more inclusive society and future for all our children.

[Cover photo © Annie Spratt]

Thank you for visiting our website. You can also keep up with our mission for #edinclusion by liking our Facebook page or following us on Twitter @StartingWJulius